Biodiversity

Learn why wolves are important to their ecosystem and why we need to save this critical keystone species from extinction.

Wolves Are a Keystone Species

Wolves are what’s referred to as a “keystone species”, which is any species that other plants and animals within an ecosystem largely depend on. If a keystone species is removed, the ecosystem would drastically change, and in some cases, collapse.

What Happens to an Ecosystem Without Wolves?

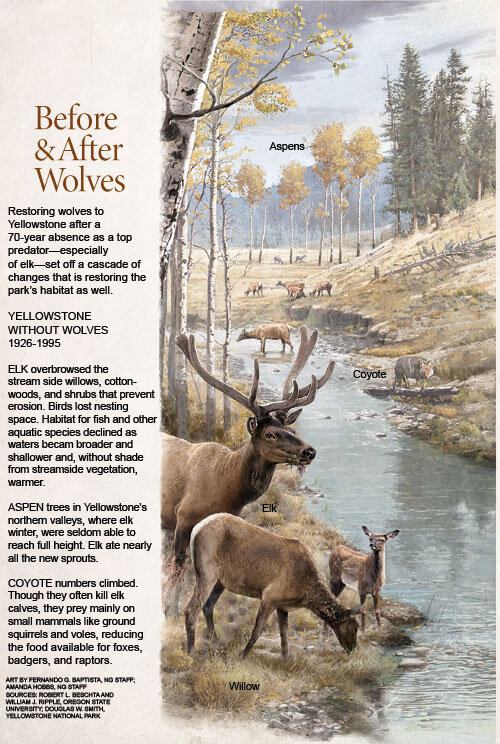

Once the dominant predator disappears from an environment, the next largest hunter will assume the top spot in the food chain. In the case of wolves, there are no large predators that fill their exact niche, and coyotes are the next species in line to take over when wolf populations decrease.

While wolves primarily prey on larger animals, due to their smaller size, coyotes specialize in hunting mid-size to smaller prey. As the coyote population explodes, the populations of foxes, badgers and martens, all of which compete with coyotes for rodents and other small game, begin to dwindle. At the same time, the large prey that were once hunted by wolves, such as elk and deer, begin to multiply excessively, stripping vegetation from highlands and decimating valuable aspen and willow cover from streams.

With fewer elk carcasses to feed on, scavengers that were previously accustomed to dining on scraps from wolf kills, such as magpies, ravens, and bears, have to scrounge elsewhere for protein.

Yellowstone Without Wolves (1926-1995)

This image was taken from the National Geographic story "Wolf Wars", published March 2010. It illustrates the lack of biodiversity in Yellowstone National Park prior to wolf reintroduction.

"The wolf is a keystone species. You remove it and the effects cascade down to the grasses."

- Douglas Smith, Yellowstone Biologist

Wolves in Yellowstone National Park

In Yellowstone, that cascade effect has long been felt. Since the 1930s, wildlife managers have watched in dismay as the park's ecosystem— once well-balanced between predator and prey—grew more and more bottom-heavy. Finally, in the 1970s, they decided to do something about it. Working through the then newly-enacted Federal Endangered Species Act, they proposed a plan under which wolves would be imported from Canada to reclaim their place in the ecosystem.

Twenty years later, the plan was approved, and wolves were captured and transported by airplane across the border, and then by truck and even by mule-drawn wagons in 1995 and 1996 to Yellowstone (31 wolves) and to Idaho (35 wolves). A third wolf population was starting to recolonize northwestern Montana by natural migration from Canada in the late 1970s-early 1980s. These three separate recovery areas provided excellent habitat for the wolves to breed and expand their territories, and today the combined wolves from these three regions are known as the Northern Rockies gray wolf population.

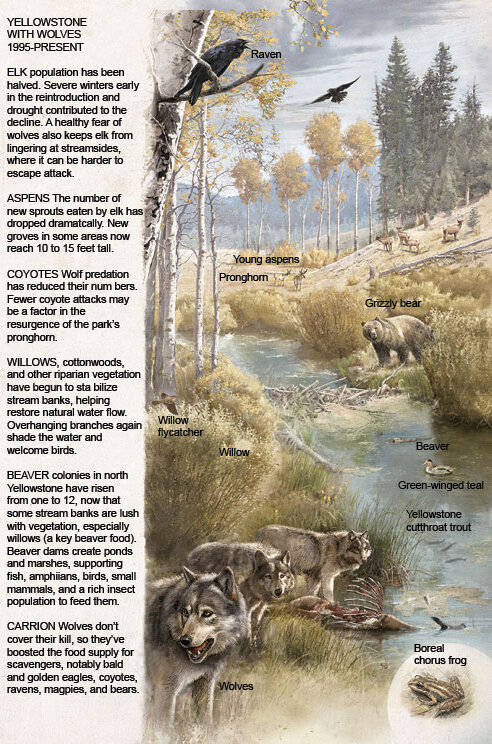

Yellowstone With Wolves (1995-present)

This image was taken from the National Geographic story "Wolf Wars", published March 2010. It illustrates the return of biodiversity in Yellowstone National Park as a result of wolf reintroduction.

The Impact of Wolves

The impact of the return of this key predator and its contribution to establishing a healthy, functioning ecosystem is now apparent in a variety of ways. Read below to learn more about the role wolves play in creating a biodiverse habitat.

Restoration of Symbiotic Relationships

Elk kills are now common around Yellowstone, a welcome development for park managers hoping to bring that animal's population back to manageable levels. The elk themselves have become more wary and less apt to stay in any one place for long periods of time.

Elk, moose and bison carcasses from wolf kills provide plenty of leftovers for other animals to scavenge. This relationship existed for thousands of years before wolves were exterminated from the park.

Ecological “Breathing Room”

This reinstated wolf presence has reduced the coyote population of the park by 50% (and even more in some areas), since wolves view other canids as territorial competition. This has opened up ecological "breathing room" for foxes and other species in areas where the coyote population had unnaturally exploded in the absence of wolves.

Recent evidence suggests that the wolf's reduction of the coyote population has even resulted in higher survivorship rates of the fawns of pronghorn antelopes, highly favored by coyotes.

Woody Riparian Habitat Regrowth

Although woody riparian habitats were mostly spared from overgrazing, booming populations of ungulates feeding on aspen and willow saplings significantly reduced their numbers. With wolves now regulating ungulate populations, these saplings can grow to adulthood. These trees not only provide nesting and roosting spots for migrating songbirds; they shade over the rivers, keeping temperatures cool and favorable for juvenile fish, roots that add stability to stream banks from erosion, and woody material used by beavers to construct dams.

"We're seeing beneficial effects from the top down. Who knows how far it will go?"

- Robert Crabtree, Wildlife Ecologist

How You Can Help Support Wolves

We can't achieve our goal of wild wolf recovery without your help! Here are some ways you can take action for wolves today.